Lord in 1845, Poe opined that “the only remarkable things about Mr. Tackling a collection of poems by William W.

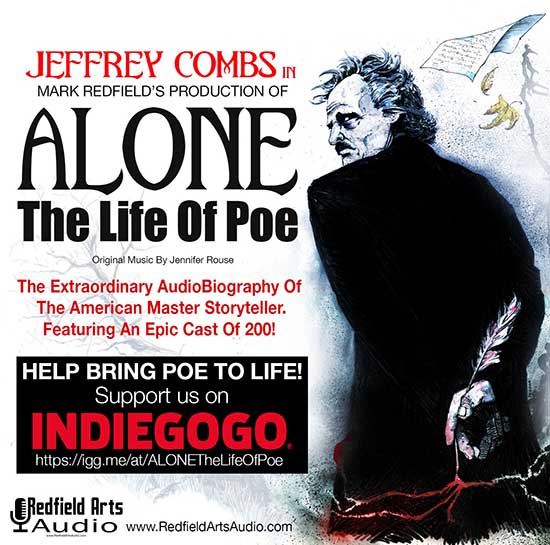

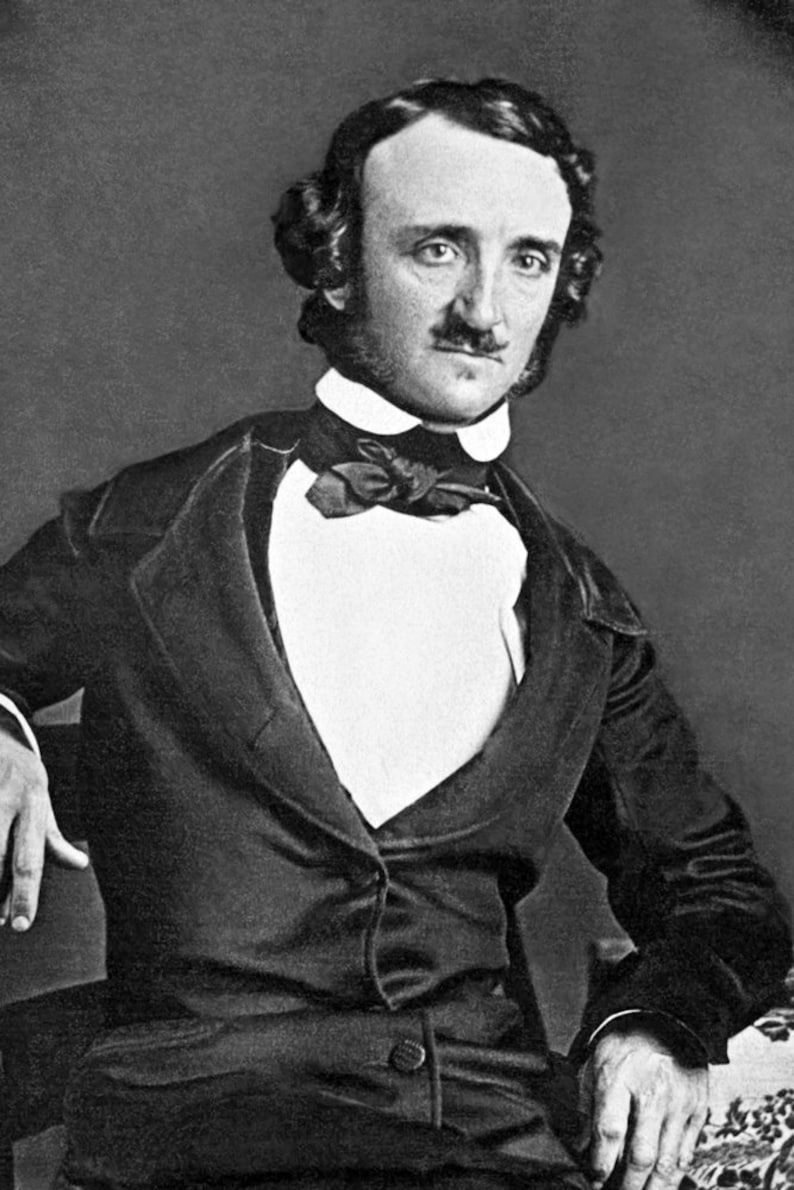

But, from 1835 until his death in 1849, the typical Poe book review sloshed with invective. He occasionally celebrated authors he admired, such as Charles Dickens and Nathaniel Hawthorne. Few outside of Poe scholarship circles bother reading them now, though in a discipline that’s had its share of so-called takedown artists, Poe was an especially unlovable literary critic. Poe churned out reams of puff-free reviews-the Library of America’s collection of his reviews and essays fills nearly 1,500 dense pages. His gloom, the film suggests, became a kind of asset for Poe, providing a tone for his stories and poetry as well as a means of attack against the “puffing” of American authors that defined much literary criticism at the time. Through dramatic readings of Poe’s work and a moody performance of Poe himself by Denis O’Hare, the film captures an author scrabbling for a place in the literary world. This struggle to make art amid his struggles-he was an orphan, an alcoholic, an academic bust at the University of Virginia and West Point, and often on the run from creditors-is the crux of the American Masters documentary Edgar Allan Poe: Buried Alive, which airs on PBS October 30. More often, Poe made his living by toiling at now-forgotten magazines like the Southern Literary Messenger, Burton’s Gentleman’s Magazine, and Graham’s Magazine.

He invented the modern detective story, successfully transported the gothic tale across the Atlantic, and wrote classic dark poems like “The Raven,” “Annabel Lee,” and “The Bells.” But, during Poe’s lifetime, such high points were intermittent, hard-fought, and rarely financial successes. Poe’s reputation as a major American writer is unassailable. And, overall, Poe wielded the kind of literary power that “can only be possessed by a man of high genius,” according to the anonymous reviewer-who was almost certainly Edgar Allan Poe himself.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)